Mistaken Identities, Part II (The Written Lecture)

September 24, 2010

by Daryl Chin

The project of historiography, especially in relation to cultural practice, has always been fraught with problems. Certainly, by the end of the 1960s, when there appeared the rise of ideological frameworks which acknowledged “difference”, we have learned that a simple assertion of historiographic completeness is a dogmatism which must be challenged. Even the theory of origins has been called into question in the epoch of post-modernism.

Quite frankly, I’ve lived long enough to see aspects of my life, from childhood on, being scrutinized and memorialized and theorized out of any semblance to the concept of “truth”. I shall give one example, which occurred to me because of the recent conference, “Performing the Future,” held from 8 July to 10 July, 2010, at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt. There was someone who has been a theorist of “queer performance,” and this is someone I’ve known for quite a while. But I remember reading one of his books, which began with a discussion of Charles Ludlam; he began by explaining how, when he first arrived in New York City, he never bothered to see Charles Ludlam’s Ridiculous Theatrical Company live. Although he arrived in New York City in 1984, when Ludlam was in the throes of his immensely productive career (Ludlam would die in 1987), he could have seen Ludlam at any time, but chose not to; but now, as a Performance Studies professional whose specialty is queer performativity, he had to theorize about Ludlam. So he did. Now, it’s one thing to write about a performance one has never seen, using archival materials to provide the evidentary content. This, in fact, is what theater research is often about: this is the process of historicization which is the foundation for theater scholarship. But it’s quite another thing to simply theorize about an artist because said artist fits within the framework of one’s theoretical precepts (even if, or especially if, one has never seen said artist’s work). It’s also suspect to theorize about an artist when, in fact, the actual performances might invalidate the theoretical presuppositions.

Performance Studies should be dealing with the manifestations of performance, providing frameworks to explicate, to interrogate, and to analyze that most ephemeral of artistic practices. This seems to be, or should be, logical. However, Performance Studies has become a catch-all for sloppy scholarship, lack of rigor, and unfounded theoretical assumptions. Be that as it may, what is important (now) in dealing with many performative manifestations is the accessibility of the artists; quite frankly, if we are dealing with performance since the 1960s, many artists are still alive, so the ability to access these artists should not be a matter of exhumation, but simply a matter of introduction.

In dealing with a phenomenon such as the Judson Dance Theater, it is important to remember the limitations of the situation at hand. Annette Michelson, in her essay “Yvonne Rainer: The Dancer and the Dance” (1974), spoke of the constraints of the New Dance: “New dance, like new film, inhabits and works largely out of Soho and those adjunct quarters which constitute the center of our commerce in the visual arts. They live and work, however, entirely on the periphery of their world’s economy, stimulated by the labor and production of that economy, with no support, no place in the structure of its market. New dance and new film have been, in part and whole, unassimilable to the commodity value. Existing and developing within their habitat as if on a reservation, they are condemned to a strict reflexiveness.” Susan Sontag, in her essay “Happenings: an art of radical juxtaposition” (1962), mentioned that in the audience “one sees mostly the same faces again and again.” To have been in the audience for many of the events that constituted “the Judson Dance Theater” turned out to be an experience which was quite circumscribed. An example: when “The Mind Is a Muscle,” Yvonne Rainer’s magnum opus from which her signature dance, “Trio A,” was introduced, had a four-evening run at the Anderson Theater on Second Avenue and Seventh Street in lower Manhattan, that means that, since the Anderson Theater (which is now the Orpheum Theater) has a seating capacity of 400, if the run was sold-out (which it never was), a maximum of 1600 people would have seen it in the spring of 1968. (In fact, according to Rainer, her estimate of the audience at all four performances would amount to 250 people.) From the possible total of 1600, the influence of “The Mind Is a Muscle” has been extraordinary. Just as an aside: attending a dance concert by Simone Forti at a venue on West 14th Street in 1974 or 1975, the audience of approximately 150 consisted mostly of other post-modern choreographers and dancers, including Yvonne Rainer, Steve Paxton, David Gordon and Valda Setterfield, Barbara Dilley, Trisha Brown, Nancy Green, Douglas Dunn, Sara Rudner and Rose Marie Wright, Carolyn Lord, Marjorie Gamso, Mary Overlie and Wendell Beavers… I remember thinking that if a bomb had gone off, most of what was called the downtown dance scene would have been wiped out. The downtown dance scene was never that big, and after a certain point, if you’d gone to the various venues (Judson Memorial Church, St. Mark’s Church in the Bowery, Clark Center, Cubiculo, La Mama E.T.C., as well as various galleries and museums, etc.), you started seeing the same faces again and again.

Though the scene was small, it was also very multifaceted, with artists ranging from people with incredible facility (Gus Solomons, Jr., Kenneth King, Deborah Hay) to people who had not studied dance until they were adults, so they didn’t have standard dance training (Rudy Perez, David Gordon, Simone Forti). And the influences, the affiliations, and the associations were also as diverse as the people involved; even taking what has become known as the Judson Dance Theater as an example, aside from the general involvement with the composition class taught by Robert Ellis Dunn, the dancers had already studied with Merce Cunningham, Alwin Nikolais, Anna Halprin, Merle Marsciano, Beverly Schmidt and Roberts Blossom. The approach to movement was never uniform; in 1968, Jill Johnston, the most dedicated chronicler of the downtown dance scene of the 1960s, wrote an essay, “Which Way the Avant-Garde?” and concluded: “The avant-garde choreographers of the sixties number a mere handful and their audience is nothing next to the droves who turn out for everything conservative; but they and their dedicated followers (many of them artists with similar concerns) tenaciously cling to the principle that revolution is not only inevitable but essential…. I’ve just barely touched on the activities of the avant-garde dance in New York. Meredith Monk, for instance, is one of the most interesting younger choreographers around. With her multiple concerns, she has been exploring the possibilities of dancy dances, of ‘found’ dances, of environmental dances, of ‘still’ images, and of intermedia work. Also dealing with imagery in an intermedia framework is painter Robert Rauschenberg. I think the question whether some of these things are dance or not is irrelevant to the vitality of a movement which, in any case, has questioned the entire fabric of traditionalist dance – both structurally and philosophically.”

One aspect of the downtown dance scene (and there was a corollary in the underground film scene) was the lecture-demonstration. One important venue for dance in the 1960s and 1970s was The New School, in a program run by Laura Foreman. The programs would often showcase three or four choreographers, who would show either a short work or a section of a longer work, and then they would be required to talk about the work, to explain their intentions and to discuss their process. This lecture-demonstration format was an extension of the methodology of the composition classes taught by Robert Ellis Dunn. Trisha Brown once said that, prior to the Judson Dance Theater, dancers simply learned the movement technique of a specific choreographer (Graham technique, Humphrey-Weidman technique, etc.) and developed their style within that technique (as Jose Limon did with Doris Humphrey and Charles Weidman), but since the Judson Dance Theater, dancers had to think, and they had to articulate what they thought. And when you went to see dance in the 1960s and 1970s, you were often given a lot of information, in the guise of notes in the program, commentaries, and addresses to the audience. Several choreographers began using the lecture-demonstration as a form for their work: three choreographers who did this were Steve Paxton and Gus Solomons, Jr. and Kenneth King. I’m just using this as an example to explain the fact that discourse, critical and analytical, was central to the downtown dance scene. It continues to this day, with the Movement Research concerts currently being held at the Judson Memorial Church, where works-in-progress are presented for discussion between the choreographers and the audience.

In trying to talk about the Judson Dance Theater, one problem has been finding evidence of the multivalence of the phenomenon. I can point to the parallel in film: in the preface to the first edition of P. Adams Sitney’s “Visionary Film”, Sitney concluded, “This book does not pretend to be exhaustive of American avant-garde film-making. Nor does it discuss the work of all the most famous and important film-makers. Major figures such as Ed Emshwiller, Stan VanDerBeek, Storm De Hirsch, and Shirley Clarke, to name a few, are not discussed here.” However, in the ensuing years since “Visionary Film” was first published in 1975, there has been few, if any, attempts to rectify Sitney’s omissions; one of the only scholars to have attempted to do justice to a more inclusive view of the avant-garde film has been Wheeler Winston Dixon with his book “The Exploding Eye”; however, most studies of the American avant-garde film have simply reiterated the basic schema of Sitney’s book.

Similarly, instead of trying to find out more about the numerous personalities involved in the Judson Dance Theater, the focus remains on those already acknowledged. When I reviewed Yvonne Rainer’s “Work 1961-73” for DanceScope (Spring 1975), I began by stating that she was not the most original choreographer of her generation (that would be Simone Forti), nor was she the most rigorous choreographer of her generation (that would be either Deborah Hay or Steve Paxton), nor was she the most fluid choreographer of her generation (that would be either Trisha Brown or Ruth Emerson), but Rainer was certainly the most comprehensive choreographer of her generation. What I discovered was that, since most people had no interest in finding out about the other choreographers of the Judson Dance Theater, the centricity of her career has singled her out, and she has received a disproportionate amount of coverage, considering the fact that the bulk of her choreographic career lasted little over a dozen years. Yet, even given this designation of Rainer as the paradigmatic figure of the Judson Dance Theater, the distortions in how her career is categorized derive from the presumptions which the commentators already have.

Rainer herself was very aware of this. In discussing the situation of Robert Rauschenberg’s association with the Judson Dance Theater, she noted, “Upon Rauschenberg’s entry – through no error in his behavior but simply due to his stature in the art world – the balance was tipped, and those of us who appeared with him became the tail of his comet…. If Bob raised his thumb it was something very special because he was doing it; if I raised my thumb, it was dancing.” So I shall make some comments which might seem to be rather strident, but in this situation, such stridency might be warranted.

I shall use Rainer’s own words as my backup. For example, the emphasis on Rainer’s career has stipulated the connections of her work to Minimal and Conceptual Art, yet her work did not start in that way. “It should be kept in mind that the literary element of my performance work… may give a somewhat distorted impression of what that work was about.” Why these distortions happened, I shall try to explain. And I’ll try to make it fast.

From the late 1960s on, Artforum became the most influential of the art magazines in the United States; though Artforum never attained the circulation numbers of the other major art magazines (Art in America, ArtNews, Arts); the reason for its influence (out of all proportion to its readership) was that, since it wasn’t the most lucrative of the art magazines, it allowed a lot of people who weren’t critics (artists and curators) to publish. Donald Judd, Robert Smithson and Robert Morris were among the artists who wrote articles for Artforum. The editorial board of Artforum included critics who exercised their influence in a variety of ways, such as curating; among these critics were Lawrence Alloway, Robert Pincus-Witten, Max Kozloff, Rosalind Krauss and Annette Michelson. Pincus-Witten, Krauss and Michelson were among the most ardent advocates for what is now known as Minimal Art; one reason was because they were critics tired of what Rosalind Krauss called the tyranny of the Existential pretensions of Abstract Expressionism and its critics, in particular, Harold Rosenberg. Krauss noted that they did not want to interpret the gestural symbolism of Abstract Expressionism, they wanted to denote the formal qualities of the paintings. (Similarly, Jill Johnston explained about the Judson Dance Theater choreographers, “They are making it clearer than ever that formalist structural concerns were always an issue and that the future of dance rests on these concerns rather than any new cult of personality or new schools of technique.”) Another reason was that, as notable educators, these critics were influencing future generations in terms of their specific formalist/structuralist approach, and that would continue throughout the five decades since the initial classes given by Robert Ellis Dunn.

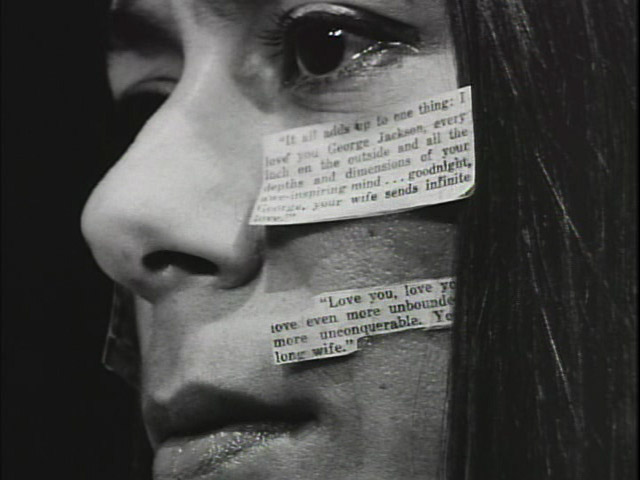

In terms of Yvonne Rainer: she had been singled out by Jill Johnston very early on in her choreographic career; she was also singled out by other critics, such as Allen Hughes of the New York Times, for one reason, because of the prolific nature of her output in the early 1960s; Annette Michelson added to the view of Rainer’s work in terms of its formalist/structuralist qualities in her essays “Yvonne Rainer, Part I: The Dancer and the Dance” (Artforum, January 1974) and “Yvonne Rainer, Part II: Lives of Performers” (Artforum, February 1974). Because (by 1971) Rainer’s work shifted into cinema, Rainer’s critical audience encompassed not just dance critics but film critics. The importance of the feminist film movement, as exemplified by such journals as Camera Obscura, coincided with Rainer’s development as a filmmaker, and she found crucial critical support among feminist film critics such as Teresa de Lauretis, Lucy Fischer and B. Ruby Rich. Those are some of the reasons as to why Rainer was singled out (in particular, her proximity to Minimal Art, as epitomized in her concerts at the Whitney Museum, “Continuous Project-Altered Daily”, which were held concurrently with Robert Morris’s sculptural exhibit of the same name); her willingness to write about her own work also provided a convenient context, especially for those people who had no prior knowledge of dance (as most film critics had not).

For me, it’s neither here nor there to determine whether or not Yvonne Rainer merited her designation as the exemplar of what we can call Post-Modern Dance. But I’d like to make an aside: in the mid-1970s, Lucinda Childs published a “portfolio” about her early works in Artforum; in the introduction, she stated that the influences on her dances were Robert Rauschenberg, Robert Morris and Yvonne Rainer. I’m not saying she’s lying, I’m saying that she’s a performer and she’s playing to her audience. She doesn’t mention Bessie Schoenberg, whom she studied with at Sarah Lawrence College; she doesn’t mention Hanya Holm, in whose company she danced while she was still in school; she doesn’t mention James Waring, in whose company she danced (along with Yvonne Rainer, Deborah Hay, David Gordon, Freddy Herko, Aileen Passloff, Toby Armour, and Arlene Rothlein); she doesn’t mention Aileen Passloff; she doesn’t mention Arlene Rothlein. In short: Childs didn’t mention any dance influences on her career, because she was writing in an art magazine, and she wanted to appeal to an art crowd.

We’re aware that the dynamics of observation can change any situation; this has caused changes in sociology and anthropology, as the notion of the detached observer has been discredited. We know that the questions that are asked often predetermine the response. The determination of the market mentality in which the art world achieves its valuation through the quantification of commercial status coincides with the ascendancy of the commercial cinema as the arbiter of cultural values. This was a situation foreshadowed by Andy Warhol. Which is to say that we know the current critical research in the area of Post-Modern Dance has stressed the proximity of the visual arts at the expense of Post-Modern Dance’s history in relation to dance and theater. Just as an example of this: one of the most important theater works in which Yvonne Rainer and Lucinda Childs were involved was the 1963 production “What Happened” based on Gertrude Stein’s piece, directed by Lawrence Kornfeld, with music by Al Carmines. In its time, “What Happened” was widely acclaimed, it was one of the highlights of the 1962-63 theater season, it played to sold-out houses at the Judson Memorial Church, and it won an Obie Award from the Village Voice. Here is Susan Sontag’s comment (from her essay “Marat/Sade/Artaud”): “We have up to now lacked a full-fledged example of Artaud’s category, ‘the theater of cruelty.’ The closest thing to it are the theatrical events done in New York and elsewhere in the last five years, largely by painters (such as Allan Kaprow, Claes Oldenberg, Jim Dine, Bob Whitman, Red Grooms, Robert Watts) and without text or at least intelligible speech, called Happenings. Another example of a work in a quasi-Artaudian spirit: the brilliant staging by Lawrence Kornfeld and Al Carmines of Gertrude Stein’s prose poem, ‘What Happened,’ at the Judson Memorial Church last year.” Yet Rainer and Childs are never asked about “What Happened”, just as they are never asked about James Waring.

But in “Work 1961-73”, Rainer did write about James Waring: “Jimmy had an amazing gift which – because I was put off by the mixture of camp and balleticism in his work – I didn’t appreciate until much later. His company was always full of misfits – they were too short or too fat or too uncoordinated or too mannered or too inexperienced by any other standards. He had this gift of choosing people who ‘couldn’t do too much’ in conventional terms but who – under his subtle directorial manipulations – revealed spectacular stage personalities. He could pull the silk purse out of the sow’s ear. At its worst, dancing with Jimmy could feel like a sow imitating a swan, but I got a lot out of it. He used what I had and demanded more than I thought I had, and his instincts were usually right. In some ways he fathomed my potential more accurately than I could at the time. Although I have often disagreed with him on matters of taste and style, I can’t dispute that he is something of a genius.” Don McDonagh, in his book “The Rise and Fall and Rise of Modern Dance”, stated: “He existed as a focal point for dance experimentation before the existence of the Judson Dance Theater and thus permitted dancers like (Paul) Taylor, Yvonne Rainer, Fred Herko, Lucinda Childs, Aileen Passloff, Deborah Hay, and Arlene Rothlein to gain valuable performance experience when few other opportunities were available to them.”

One fascinating fact is that the discrepancy in the economic situation has been central to the research: off-Broadway theater was never exactly a lucrative enterprise, while the art world, certainly since the 1960s, has been one source of advanced material wealth. And so there has been a corresponding discrepancy in the way that scholarship has followed the money; if we take the annual conferences of the Association of Theater in Higher Education and the College Art Association as indicators, the amount of research being devoted to contemporary theater and to contemporary art is disproportionate, to say the least. And so it should come as no surprise that students researching the Judson Dance Theater would focus on the association with the art world, specifically with the successful artists such as Robert Rauschenberg and Robert Morris, rather than with the composers and musicians who had been part of the Judson Dance Theater, such as Malcolm Goldstein, Philip Corner, John Herbert McDowell, and James Tenney. (It’s significant that Alex Hay, Carol Summers and Carolee Schneemann, three other artists closely associated with the Judson Dance Theater, have not been investigated to the extent of their involvement, and Charles Ross, the sculptor who created one of the most significant collaborations with the Judson Dance Theater, has been totally ignored. I should amend that to say that the rise in feminist studies in art history and in performance studies brought a great deal of attention to Carolee Schneemann in the last two decades.) The collusion of economic success as an arbiter of artistic merit has infected the valuation of recent art history, and that infection has proven contagious in most dealings with the history of the Judson Dance Theater.

And so the connections that the Judson Dance Theater had to the developing off-off-Broadway scene have been elided if not outright erased. The Judson Dance Theater as a site for the experimental music scene prior to the formation of Fluxus has also been neglected.

I don’t mean to single out Yvonne Rainer, but since she’s already been singled out, I might as well just add fuel to the fire.

For example: though Yvonne Rainer did include films and slides in her work, she was not primarily interested in multimedia work. That would be Beverly Schmidt and Roberts Blossom (the Schmidt-Blossom Dance Company, which existed from 1960 until 1965; Rainer was in the company for a period), then Elaine Summers and then Meredith Monk. Actually, Yvonne Rainer had no great interest in “ordinary movement”. Jill Johnston (“Which Way the Avant-Garde?”): “If the most revolutionary proposition of the new dance was that any sort of movement, or action, or any kind of body (nondancer as well as dancer) was acceptable as material proper to the medium, it was also true that certain choreographers remained in some dialectical relation to tradition, retaining a technical basis for movement while seeking to transform the outmoded structuring of conventional techniques. One of the most encouraging aspects of recent developments is a reassertion of a concern for such movement – as it is still understood in the context of the dance tradition – in a programmatic effort to define it in truly contemporary terms.” (Johnston cited Yvonne Rainer, Deborah Hay and Lucinda Childs as choreographers who “have recently attacked the problem of advancing the medium within a sphere that lies somewhere between ordinary action (anybody can do it) and a more dance-based idiom.”) Yvonne Rainer herself has explained, “I guess the range of my interests was quite a bit broader than was many other people’s in the workshop (Robert Dunn’s composition class). I mean just in terms of my personal performance and in terms of my choreographic work for a group. Like doing a dance that just consisted of running. That seems a novel idea but, unlike Steve Paxton who did a dance that consisted only of walking, I was still wedded to or interested in undermining or making reference to certain kinds of theatricality that I was then becoming more and more in opposition to.” If Rainer was interested in ordinary movement, it was in relation to, in dialectical opposition to “traditional” dance. Similarly, “task performance” was never a focus for Rainer’s work, but only in relation to traditional dance movement. Simone Forti is credited with coming up with the idea of “task performance” and she created pieces in which the action was the focus in and of itself, but for Rainer, a task was always embedded in a theatrical work (as opposed to Forti, where the task was the theatrical work).

My point is that if you look at the work (even in terms of its excavation as art historical artifacts), you will come to a broader understanding, not just of (say) Yvonne Rainer’s actual achievement, but her connections to the broader cultural scene of the time. I’ll give an example of the Schmidt-Blossom Dance Company. Beverly Schmidt was a principal dancer with Alwin Nikolais in the 1950s; she began to present her own work in the mid-1950s, and soon was joined by her husband, the actor Roberts Blossom. Beverly Schmidt also started teaching at Sarah Lawrence in the late 1950s, and one of her students was Lucinda Childs. Lucinda Childs has mentioned how Beverly Schmidt was one of the dancers that people were interested in seeing in the late 1950s, because her work seemed so original. The original aspect of her work included the incorporation of media in her pieces, not just lighting effects and slides (which had been a signature of Nikolais’s work), but also film. Schmidt herself was a very strong and very lyrical dancer, but the media aspects of her work were handled by her husband, Roberts Blossom. Quite frankly: sometime in 1960, he got the idea that film could be used in a theatrical presentation. He’d helped his wife with lighting effects and slides (which derived from Nikolais), but the idea of using a moving image as part of the theater… it’s hard to explain, but nobody had ever done that before, but Roberts Blossom got that idea. And so Roberts Blossom began to develop pieces with his wife which would incorporate film. (Robert Whitman began using film in 1961, and is usually credited as the person who started using film as a multimedia element in performance.) People were so excited that many people sought out the Schmidt-Blossom Dance Company, because they wanted the chance to work with someone who was so original. (Some of the people who worked with Beverly Schmidt and Roberts Blossom include Yvonne Rainer, Meredith Monk, and Phoebe Neville.) Yet Roberts Blossom’s name has been all but eradicated from histories of dance, art, theater and performance. Why? In the mid-1960s, Beverly Schmidt and Roberts Blossom divorced; Schmidt went onto teach (she still performs on occasion) and Blossom returned to his career as an actor. In the theater, he worked with Peter Brook; in film, he has worked with Steven Spielberg (CLOSE ENCOUNTERS OF THE THIRD KIND), Jonathan Demme (CITIZENS BAND), Don Siegel (ESCAPE FROM ALCATRAZ), among others. The divorce was (by all accounts) one of those acrimonious trainwrecks. Beverly Schmidt has been interviewed about her connections with the Judson Dance Theater, but Roberts Blossom has been ignored. And this points to the biases that have developed in theater and dance research, in which performance theory now stresses gender issues. So in the case of Roberts Blossom: you have a white straight male who is not an “artist” but an “actor”. It doesn’t matter that he was one of the most original artists of his generation, he doesn’t fit into the proper categories and so he must be totally erased from the public record.

And so, in confronting the situation of the historicizing of the Judson Dance Theater, I am faced with the constant erasures, elisions, and omissions which have now become compounded by continual repetition of the same misinformation. I used the analogy with “underground film”: it’s true that I was (and am) friends with many filmmakers, including Bruce Baillie, Ken Jacobs, Robert Breer, Ernie Gehr, and Jonas Mekas (whom P. Adams Sitney wrote about in “Visionary Film”); but I am also friends with Tom Chomont and James Benning (whom P. Adams Sitney did not write about). I don’t take anything for granted, and I certainly don’t take another person’s pronouncements as gospel about people and places with which I have been familiar first-hand.

So if you look at Yvonne Rainer’s career, you won’t just get Robert Morris and Robert Rauschenberg, you’ll get James Waring. Waring was the quintessential Greenwich Village choreographer in the late 1950s and 1960s: he worked with many of the New York poets, including Frank O’Hara, Diane Di Prima, and Kenneth Koch; he worked with the Living Theater (Julian Beck designed sets for some of Waring’s dances); he collaborated with a lot of artists, including Red Grooms, Allan Kaprow, Al Hansen, Robert Indiana, Larry Poons, George Brecht, Robert Watts, and Robert Whitman. Before his untimely death in 1975, he had disbanded the idea of working with his own company, but was creating dances for other dance groups, but the men who were in his company just before it disbanded formed a company which premiered in 1974, and it was called the Ballets Trocadero! (Talk about camp and balleticism, as Rainer characterized Waring’s work.) Before she decided on a career in dance, Yvonne Rainer studied acting, first with Lee Grant, and then with Paul Mann, and throughout the early 1960s, there were occasions when she worked in theater, not just the case of “What Happened” but also the collaboration with the actor Larry Loonin on a two-character play called “Incidents” (which was performed at the Caffe Cino). You don’t just get her connection to art, but to theater and to dance. I gave the example of the dance “We Shall Run”: if you look at the cast, you’ll notice that all the women in it were dancers, Trisha Brown, Lucinda Childs, June Ekman, Ruth Emerson, Sally Gross, Deborah Hay, and Carol Scothorn, and the idea of dancers performing an action like running is very different from people with untrained bodies running. And Rainer herself acknowledged this when she said she was trying to create this movement in relation to a theatricality that she was in opposition to.

The distortions of critical response to Rainer’s career come from the initial advocacy of the Artforum critics, in particular, Rosalind Krauss and Annette Michelson. During the 1960s, Krauss was living in Connecticut, and Annette Michelson was the Parisian arts editor for the New York Herald Tribune until 1966, when she returned to New York City. Quite frankly: they never saw the bulk of Yvonne Rainer’s work as a choreographer and dancer during the period when she was most active. When Krauss saw Rainer’s work, it was when Rainer performed at the Wadsworth Atheneum under the auspices of Robert Rauschenberg, so her perception of Rainer is filtered through this art world slant. And if Michelson saw Rainer’s work when it toured in Europe, it would have been under museum and gallery sponsorship, which came from the presentation of work by Rauschenberg and Morris on the same program. And Michelson is presuming a lot about Rainer from Michelson’s critical partisanship of Minimal Art, particularly in relation to Donald Judd and Robert Morris. And the prejudices of Krauss and Michelson have filtered down through their students, who include Noel Carroll and his wife, Sally Banes. This is not to dismiss Sally Banes’s work, which I think is of vital importance: “Terpsichore in Sneakers”, “Democracy’s Body” and “Greenwich Village 1963” are three of the best works of dance scholarship that I know. But there are omissions, and people should be aware of that fact. And so there are areas of research that remain to be explored and investigated, and that is the point I’m trying to make.

—Daryl Chin

Berlin, June 2010-Brooklyn, September 2010

Bibliography

Banes, Sally: DEMOCRACY’S BODY: JUDSON DANCE THEATER, 1962-1964. Duke University Press, Durham and London, 1993.

—–: TERPSICHORE IN SNEAKERS: POST-MODERN DANCE. Houghton Mifflin, Boson 1980.

Dixon, Wheeler Winston: THE EXPLODING EYE: A RE-VISIONARY HISTORY OF 1960s AMERICAN EXPERIMENTAL CINEMA. State University of New York Press, New York 1998.

Johnston, Jill: MARMALADE ME (revised and expanded edition). Wesleyan University Press, Hanover and London, 1998.

McDonagh, Don: THE RISE AND FALL AND RISE OF MODERN DANCE. Outerbridge & Dienstfrey, New York, 1970.

Rainer, Yvonne: WORK 1961-73. Presses of Nova Scotia College of Art & Design and New York University, Halifax and New York, 1974.

—–: THE FILMS OF YVONNE RAINER. Indiana University Press, Bloomington and Indianapolis, 1989.

—–: A WOMAN WHO… ESSAYS, INTERVIEWS, SCRIPTS. PAJ Books: Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore and London, 1999.

Sitney, P. Adams: VISIONARY FILM: THE AMERICAN AVANT-GARDE 1943-2000. Oxford University Press, London, 2002.

Sontag, Susan: AGAINST INTERPRETATION. Farrar Straus Giroux, New York, 1966.

DARYL CHIN is an artist and writer living in Brooklyn; from October 2009 to July 2010, he was a Fellow at the International Research Center: Interweaving Performance Cultures at the Freie Universität Berlin.

Mistaken Identities, Part I (co-author: Larry B. Qualls) was a lecture given at the Performing Tangier 2010 Conference: New Perspectives on Site Specific Art in Arabo-Islamic Contexts in May 2010.

» A Piece

⊕

Comments Off on Mistaken Identities, Part II (The Written Lecture)

1 Comment

1 Comment