The Art Hugger

July 16, 2010

By Tobey Albright in collaboration with Chris

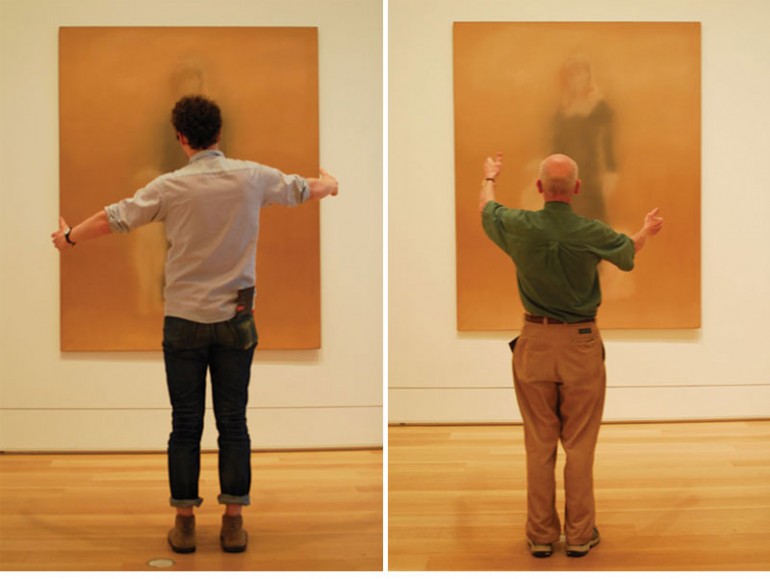

A photograph of an early art hug taken by a museum attendee.

On February 29th 1940, Theodor Adorno wrote to Walter Benjamin that “all reification is a forgetting: objects become purely thing-like the moment they are retained for us without the continued presence of their other aspects: when something of them has been forgotten.” Adorno and Benjamin were deeply attached to their artwork as a ‘thing’, autonomous and self-explanatory, yet in this correspondence a spatial potential is suggested where the work of art is much more than just an object or economic product. Within “continued presence of their other aspects,” the infamous ‘aura’ that a work of art emits [i.e. in opposition of this eliminated element during mechanical reproduction] is understood through the atmospheric apparatus of its environment, as the support structure, which renders possible an object/product.

Chris, who has requested to remain partially anonymous, could care less about the theoretical remainder that comes with each work of art. Yet, to say that he could care less doesn’t mean that he discounts such pursuits, but rather it’s just simply not what he cares with. It’s through the framework of ‘caring with’ that we understand what Chris does and why he does it. Chris is what we will call an “art hugger.” And up until the point when I first met him, at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago, I was unaware that such an activity existed. Much as we can imagine, hugging art is not possible in a museum, as they have policies outlined to protect each work of art for future generations: “Please allow a distance of 12 inches from artwork. Do not touch artworks, frames, or cases, or point with canes, pencils, or other objects.” To uphold these policies is a number of mostly stationary, silent watchers. These security guards ensure that museum safety and etiquette rules are followed at all times, in addition to accelerating the awareness of each visitor’s self-awareness during their viewing experience. This triad of perceptual positions [e.g. the viewer, the guard, the art] is what Chris claims to be responsible for the hugs, as his first hug was improvised when standing in front of a Matisse painting and feeling what he could only describe as something similar to intense love and affection.

Reflecting upon his first art hug, Chris stated, “I wanted to do what anyone does when they feel love for someone, but I realized quickly that I couldn’t, or shouldn’t, and that I needed to do something in between what was so natural to me and what was understood to be illegal.” So in an attempt to resolve a complicated feeling, Chris stretched out his arms, as he stood there in front of the painting, and imagined that he was embracing it like any lover, family member, or friend. This imaginary hug gesture gave him the ability to feel as though he were able to reciprocate his feeling, and for the first time he felt as though he could experience the art personally and intimately, rather than coldly and institutionally. He went on to say that the first couple of hugs opened up a space between he and the work of art that was so engaging and enthralling that he forgot he was in a public space altogether. “By the third or fourth hug I quickly remembered that I was hugging the art in front of other people and I started to notice how their countenance was both puzzled and joyful because of my hugging,” recalls Chris. He noticed that other museum goers started to take pictures of his embrace, in addition to adopting his hugging behavior for their own affectionate improvisations. And here it’s important to note that Chris has never photographed himself during a hug, because as he states, “I don’t want people to think that this is art; that this is some parasitic performance.” He explained this by adding, “I’m doing this for myself, for the art and for everyone who loves it, because having a postcard on your refrigerator at home doesn’t adequately express the love we can feel for something or someone.”

Photographs shared with Chris, both of and by the photographer, via flickr.

Like anyone who starts to get close to someone or something, Chris wanted to get as close as possible in order to intensify his expression of affection. By his eighth hug, Chris enlisted the help of a friend to assist him in identifying a period of time in which the assigned security guard was inattentive and Chris could get closer to the work. During this, his most successful hug, Chris was able to hover his body, with outstretched arms, four inches above Cy Twombly’s “Untitled,” 2003. After a period of 17 seconds, a quick coughing spell with three successive shifts in volume alerted Chris that the guard was moving back in his direction and his embrace was released. On a number of occasions Chris has been stopped mid-hug by the guard on duty. Even after attempting to start a conversation regarding the ethical quality of his intentions, each of the guards suggested that repeat behavior could find Chris kicked out of the museum and never permitted reentrance. One guard went on to explain to Chris that if he were to touch the work of art, or perhaps even accidentally fall into it, he may receive a possible charge of felony damage that carries a maximum sentence of three and a half years in prison.

The difficulty with art hugging becoming a widespread institutionally accepted behavioral trend lies in the potential for it to be considered an act of art terrorism, where the proximity of the hugger and the art is simply too close for comfort. There is after all, a growing list of near priceless works that have been damaged at the hands of careless accidents. The most recent is the Met’s Picasso painting “The Actor,” which was torn when a woman attending an adult-education class lost her balance and fell onto the large canvas. Other cases include another Picasso painting, “Le Rêve,” (valued at $139 million) which was elbowed accidentally by its owner in 2006, and Tate Britain’s sculpture by Carl Andre, “Venus Forge” (a series of steel and copper tiles placed on the ground; valued at $2.6 million) which was vomited on top of by a child.

And then, there are the earnest art terrorists— themselves; those individuals that harm works of art intentionally. Typically these individuals are simply just vandals, but on occasion an iconoclast will damage with intent to weaken religious or political institutions by attacking the conventions central to the institution’s authority. The most recent example of iconoclast attacks is the destruction of frescoes and the statues of Buddha in the Bamiyan province of Afghanistan, by the Taliban in 2001.

Additionally, art damage can occur via the framework of a performative art spectacle. In 1996, Jubal Brown ate blue cake icing and blue Jell-O in order to projectile vomit the color blue onto Piet Mondrian’s “Composition in Red, White, and Blue.” Regarding his artistic act that occurred in the MoMA, the twenty-two year old art student said, “I found its lifelessness threatening and it made me sick.” Six months prior, he vomited the color red on Raoul Dufy’s Harbour “at le Havre,” in the Art Gallery in Ontario.

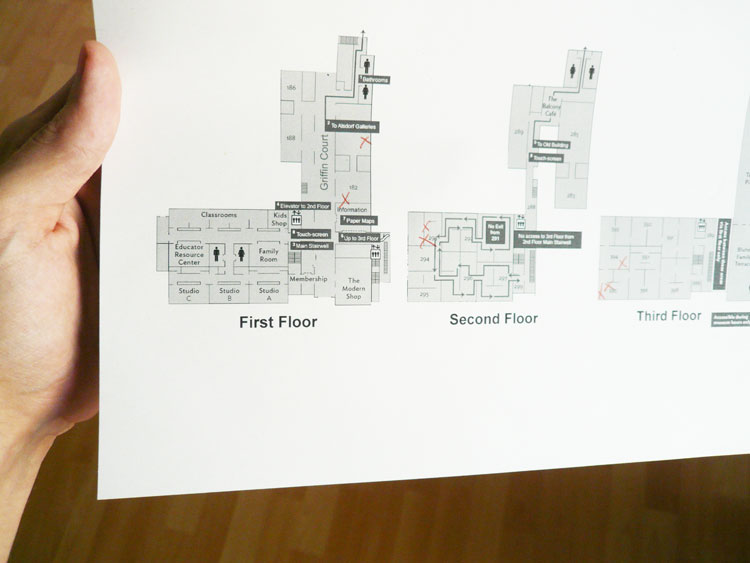

Chris’ map of hugged artworks in the modern wing of the Art Institute of Chicago.

While seemingly far removed from the good-natured art hugging behavior, the history of accidental abuse and violent actions helps us understand what the hugging is up against, in so far as the environment that contains the art must be considered to be as dangerous as it is safe, and why art hugging must occur in the semi-privacy of institutionally unsupervised experience.

Yet with all things considered, art hugging is a brilliant example of the improvisational appropriation that human beings enact with the hope of rendering creative productions useful. By understanding Chris’ intentions we might consider his hugs an evolutionary extension of Benjamin’s ‘aura’. Perhaps art hugging is a psychic spatial phenomenon that unifies dual projections, or auras of the self and its other/art. But after sharing this thought with Chris, he doesn’t think so. To him, he is simply “making love with the art.”

» A Piece

⊕

Comments Off on The Art Hugger